Sunday, May 01, 2005

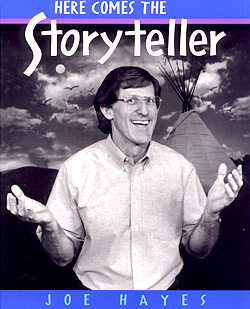

Joe Hayse, The Man!

Ok, when I was a little girl and lived in Albuquerque, I would visit my Grandparents (and Mexican food stand couple/family friends Rocky and Mona) in Santa Fe. Here in this artistic haven resides a famous storyteller, Joe Hayes. Now, when I was small, my family would take me to go listen to Joe, whether he be at an art museum, a park or at an evening party. I can just remember the stones we sat on as the sun set and the air became brisk. I remember a fire. I remember hot blue days where the smell of pinon trees settled in the blistering heat, and I sat and listened to Joe with all the other children.

He would tell us about Coyote and the mice, and Buzzard and Rabbit with his pitch and Horn Toad inside a stomache. I can remember how magical it was to listen to this elderly handsome man with his amazing expressions and voice.

Anyway, I would recomend that everyone should check up on Mr. Hayse if you are ever in Santa Fe. I know I will when I visit this summer.

A little bit about Joe Hayes:

Joe Hayes is one of America's premier storytellers-a nationally recognized teller of tales from the Hispanic, Native American and Anglo cultures. His bilingual Spanish-English tellings have earned him a distinctive place among America's storytellers. His books and tapes of Southwestern stories are popular nationwide. Joe's tales combine the traditional lore of the American Southwest and his own imagination. The traditional part is based on things people have told him and on what he has learned from reading the work of folklorists and anthropologists. Most of the material he uses was collected fifty or more years ago, before radio, television and movies began to replace the old stories. Joe's own contribution is based on his instincts as a storyteller and what his experience tells him listeners need in order to feel satisfied with a story. The stories reflect his own values and sense of humor, as well as the values and humor of Southwest cultures, which is made up primarily of Hispanic, Native American and Anglo cultures.

By Master Storyteller Joe Hayes

From his book “The Day It Snowed Tortillas”

Once in a small mountain village there lived two men who were good friends. The one man’s name was Pedro. The other? Well—no one remembered his name. You see, no one ever called him by his name. Instead, they used his nickname.

Back when he was only 7 or 8 years old, everyone had started calling him El Diablo—The Devil—because he was so mischievous.

In school, if there was some prank being played on the teacher, you could bet that El Diablo thought the whole thing up. He would get all the other boys involved, and they’d all get caught and get in trouble. And even when they were grown men and should have known better, it was still happening. El Diablo was leading Pedro astray.

For example, there was the time that El Diablo said to his friend, “Pedro, have you noticed that the apples on Old Man Martinez’s tree? They look wonderful. Let’s go steal some tonight. There’s no moon. No one will see us.”

Pedro said, “Oh, no! Old Man Martinez has that big dog. He’ll bite my leg off!”

But El Diablo told him, “Don’t worry about that dog. He keeps him inside at night. Come on. Let’s get some apples.” And he talked his friend into it.

That night the two friends got a big gunnysack and crept into Old Man Martinez’s yard. They filled that sack with apples, then slipped back out onto the road.

Pedro whispered, “We’ll have to find some place to divide these apples up.”

Of course El Diablo had a great idea. “I know. We’ll go to the camposanto, to the graveyard. Nobody will bother us there!”

So they went down the road until they came to the cemetery. They went in through the gate and walked along the low adobe wall that surrounded the graveyard until they found a dark, shadowy place right next to the wall.

They sat down and dumped out the apples and started to divide them into two piles. As they divided the apples, they whispered, “One for Pedro—one for Diablo … One for Pedro—one for Diablo …,” making two piles of apples.

Now it just so happened that a couple of men from the village had been out living it up that night—dancing and celebrating and drinking a little too much. In fact, they had got so drunk they couldn’t make it home. They had fallen asleep leaning against that wall right over from where Pedro and Diablo were dividing up the apples.

One man was a big, round, fat fellow. The other was old and thin, with a face that was dry and withered-looking.

A few minutes later, the old man woke up. From the other side of the wall, over in the graveyard, he heard a voice saying, “One for Pedro—one for Diablo … One for Pedro—one for Diablo …”

The poor man’s eyes popped out like two hard-boiled eggs. “Aaaiii, Dio Mio!” he gasped, Saint Peter and the Devil are dividing up the dead souls in the camposanto!”

He woke his friend up, and the two men sat there staring, their mouths gaping, too frightened to speak. The voice went on: “One for Pedro—one for Diablo … One for Pedro—one for Diablo …”

Until finally Pedro and El Diablo got to the bottom of the pile of apples. The two men heard Diablo’s voice say, “Well, Pedro, that’s all of them.”

But Pedro happened to notice two more apples, right next to the wall. One was a nice, round, fat apple. The other wasn’t so good—it was sort of withered up.

The two men heard Pedro say, “No, Diablo, there are still two more. Don’t you see those two right next to the wall—the big fat one and the withered-up one?”

The hair stood up on the back of those men’s necks! They thought they were the ones being talked about. They listened for what would be said next, and they heard Diablo say, “Well, Pedro, you can take the fat one. I’ll take the withered-up one.”

Then they heard Pedro say, “No, Diablo. Neither one is any good. You can take them both!”

When the two men heard that, they thought the Devil would be coming over the wall any minute to get them. They sobered up in a hurry, jumped to their feet and ran home as fast as they could. They slammed the doors and locked them up tight!

And from that day on, the people say, those two men stayed home every night. And they never touched another drop of whiskey for the rest of their lives!

Ok, when I was a little girl and lived in Albuquerque, I would visit my Grandparents (and Mexican food stand couple/family friends Rocky and Mona) in Santa Fe. Here in this artistic haven resides a famous storyteller, Joe Hayes. Now, when I was small, my family would take me to go listen to Joe, whether he be at an art museum, a park or at an evening party. I can just remember the stones we sat on as the sun set and the air became brisk. I remember a fire. I remember hot blue days where the smell of pinon trees settled in the blistering heat, and I sat and listened to Joe with all the other children.

He would tell us about Coyote and the mice, and Buzzard and Rabbit with his pitch and Horn Toad inside a stomache. I can remember how magical it was to listen to this elderly handsome man with his amazing expressions and voice.

Anyway, I would recomend that everyone should check up on Mr. Hayse if you are ever in Santa Fe. I know I will when I visit this summer.

A little bit about Joe Hayes:

Joe Hayes is one of America's premier storytellers-a nationally recognized teller of tales from the Hispanic, Native American and Anglo cultures. His bilingual Spanish-English tellings have earned him a distinctive place among America's storytellers. His books and tapes of Southwestern stories are popular nationwide. Joe's tales combine the traditional lore of the American Southwest and his own imagination. The traditional part is based on things people have told him and on what he has learned from reading the work of folklorists and anthropologists. Most of the material he uses was collected fifty or more years ago, before radio, television and movies began to replace the old stories. Joe's own contribution is based on his instincts as a storyteller and what his experience tells him listeners need in order to feel satisfied with a story. The stories reflect his own values and sense of humor, as well as the values and humor of Southwest cultures, which is made up primarily of Hispanic, Native American and Anglo cultures.

By Master Storyteller Joe Hayes

From his book “The Day It Snowed Tortillas”

Once in a small mountain village there lived two men who were good friends. The one man’s name was Pedro. The other? Well—no one remembered his name. You see, no one ever called him by his name. Instead, they used his nickname.

Back when he was only 7 or 8 years old, everyone had started calling him El Diablo—The Devil—because he was so mischievous.

In school, if there was some prank being played on the teacher, you could bet that El Diablo thought the whole thing up. He would get all the other boys involved, and they’d all get caught and get in trouble. And even when they were grown men and should have known better, it was still happening. El Diablo was leading Pedro astray.

For example, there was the time that El Diablo said to his friend, “Pedro, have you noticed that the apples on Old Man Martinez’s tree? They look wonderful. Let’s go steal some tonight. There’s no moon. No one will see us.”

Pedro said, “Oh, no! Old Man Martinez has that big dog. He’ll bite my leg off!”

But El Diablo told him, “Don’t worry about that dog. He keeps him inside at night. Come on. Let’s get some apples.” And he talked his friend into it.

That night the two friends got a big gunnysack and crept into Old Man Martinez’s yard. They filled that sack with apples, then slipped back out onto the road.

Pedro whispered, “We’ll have to find some place to divide these apples up.”

Of course El Diablo had a great idea. “I know. We’ll go to the camposanto, to the graveyard. Nobody will bother us there!”

So they went down the road until they came to the cemetery. They went in through the gate and walked along the low adobe wall that surrounded the graveyard until they found a dark, shadowy place right next to the wall.

They sat down and dumped out the apples and started to divide them into two piles. As they divided the apples, they whispered, “One for Pedro—one for Diablo … One for Pedro—one for Diablo …,” making two piles of apples.

Now it just so happened that a couple of men from the village had been out living it up that night—dancing and celebrating and drinking a little too much. In fact, they had got so drunk they couldn’t make it home. They had fallen asleep leaning against that wall right over from where Pedro and Diablo were dividing up the apples.

One man was a big, round, fat fellow. The other was old and thin, with a face that was dry and withered-looking.

A few minutes later, the old man woke up. From the other side of the wall, over in the graveyard, he heard a voice saying, “One for Pedro—one for Diablo … One for Pedro—one for Diablo …”

The poor man’s eyes popped out like two hard-boiled eggs. “Aaaiii, Dio Mio!” he gasped, Saint Peter and the Devil are dividing up the dead souls in the camposanto!”

He woke his friend up, and the two men sat there staring, their mouths gaping, too frightened to speak. The voice went on: “One for Pedro—one for Diablo … One for Pedro—one for Diablo …”

Until finally Pedro and El Diablo got to the bottom of the pile of apples. The two men heard Diablo’s voice say, “Well, Pedro, that’s all of them.”

But Pedro happened to notice two more apples, right next to the wall. One was a nice, round, fat apple. The other wasn’t so good—it was sort of withered up.

The two men heard Pedro say, “No, Diablo, there are still two more. Don’t you see those two right next to the wall—the big fat one and the withered-up one?”

The hair stood up on the back of those men’s necks! They thought they were the ones being talked about. They listened for what would be said next, and they heard Diablo say, “Well, Pedro, you can take the fat one. I’ll take the withered-up one.”

Then they heard Pedro say, “No, Diablo. Neither one is any good. You can take them both!”

When the two men heard that, they thought the Devil would be coming over the wall any minute to get them. They sobered up in a hurry, jumped to their feet and ran home as fast as they could. They slammed the doors and locked them up tight!

And from that day on, the people say, those two men stayed home every night. And they never touched another drop of whiskey for the rest of their lives!

Memorization Feat

For my memorization feat, I memorized the poem "Darkness" by Lord Byron. If you want to hear it for some reason please proposition me with chocolate or puppies... or chocolate covered puppies... either way

Here it is in full form:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went--and came, and brought no day,

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chill'd into a selfish prayer for light:

And they did live by watchfires--and the thrones,

The palaces of crowned kings--the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum'd,

And men were gather'd round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other's face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos,and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain'd;

Forests were set on fire--but hour by hour

They fell and faded--and the crackling trunks

Extinguish'd with a crash--and all was black.

The brows of men by the despairing light

Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits

The flashes fell upon them; some lay down

And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest

Their chins upon their clenched hands, and smil'd;

And others hurried to and fro, and fed

Their funeral piles with fuel, and look'd up

With mad disquietude on the dull sky,

The pall of a past world; and then again

With curses cast them down upon the dust,

And gnash'd their teeth and howl'd: the wild birds shriek'd

And, terrified, did flutter on the ground,

And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes

Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawl'd

And twin'd themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless--they were slain for food.

And War, which for a moment was no more,

Did glut himself again: a meal was bought

With blood, and each sate sullenly apart

Gorging himself in gloom: no love was left;

All earth was but one thought--and that was death

Immediate and inglorious; and the pang

Of famine fed upon all entrails--men

Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh;

The meagre by the meagre were devour'd,

Even dogs assail'd their masters, all save one,

And he was faithful to a corse, and kept

The birds and beasts and famish'd men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead

Lur'd their lank jaws; himself sought out no food,

But with a piteous and perpetual moan,

And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand

Which answer'd not with a caress--he died.

The crowd was famish'd by degrees; but two

Of an enormous city did survive,

And they were enemies: they met beside

The dying embers of an altar-place

Where had been heap'd a mass of holy things

For an unholy usage; they rak'd up,

And shivering scrap'd with their cold skeleton hands

The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath

Blew for a little life, and made a flame

Which was a mockery; then they lifted up

Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld

Each other's aspects--saw, and shriek'd, and died--

Even of their mutual hideousness they died,

Unknowing who he was upon whose brow

Famine had written Fiend. The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless--

A lump of death--a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirr'd within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropp'd

They slept on the abyss without a surge--

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir'd before;

The winds were wither'd in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish'd;

Darkness had no needOf aid from them--She was the Universe.

Here it is in full form:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went--and came, and brought no day,

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chill'd into a selfish prayer for light:

And they did live by watchfires--and the thrones,

The palaces of crowned kings--the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum'd,

And men were gather'd round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other's face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos,and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain'd;

Forests were set on fire--but hour by hour

They fell and faded--and the crackling trunks

Extinguish'd with a crash--and all was black.

The brows of men by the despairing light

Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits

The flashes fell upon them; some lay down

And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest

Their chins upon their clenched hands, and smil'd;

And others hurried to and fro, and fed

Their funeral piles with fuel, and look'd up

With mad disquietude on the dull sky,

The pall of a past world; and then again

With curses cast them down upon the dust,

And gnash'd their teeth and howl'd: the wild birds shriek'd

And, terrified, did flutter on the ground,

And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes

Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawl'd

And twin'd themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless--they were slain for food.

And War, which for a moment was no more,

Did glut himself again: a meal was bought

With blood, and each sate sullenly apart

Gorging himself in gloom: no love was left;

All earth was but one thought--and that was death

Immediate and inglorious; and the pang

Of famine fed upon all entrails--men

Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh;

The meagre by the meagre were devour'd,

Even dogs assail'd their masters, all save one,

And he was faithful to a corse, and kept

The birds and beasts and famish'd men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead

Lur'd their lank jaws; himself sought out no food,

But with a piteous and perpetual moan,

And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand

Which answer'd not with a caress--he died.

The crowd was famish'd by degrees; but two

Of an enormous city did survive,

And they were enemies: they met beside

The dying embers of an altar-place

Where had been heap'd a mass of holy things

For an unholy usage; they rak'd up,

And shivering scrap'd with their cold skeleton hands

The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath

Blew for a little life, and made a flame

Which was a mockery; then they lifted up

Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld

Each other's aspects--saw, and shriek'd, and died--

Even of their mutual hideousness they died,

Unknowing who he was upon whose brow

Famine had written Fiend. The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless--

A lump of death--a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirr'd within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropp'd

They slept on the abyss without a surge--

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir'd before;

The winds were wither'd in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish'd;

Darkness had no needOf aid from them--She was the Universe.

Saturday, April 30, 2005

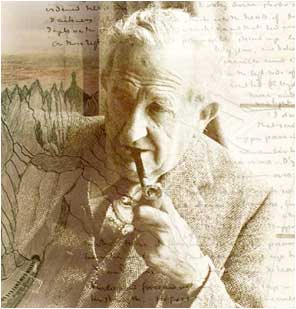

My Tolkien paper 1/ Tolkien and the Anglo-Saxon (read for oral trad. content)

Among all of the influences which the work of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien is attributed to, that of the Anglo-Saxon language and history is one of the most prominent. When compared with old forms of literature and myth, the Old English style shows itself frequently throughout the entire collection of Tolkien’s works, whether it be in names of people, places or things. His vast interest in this field of study is essential to look at to understand his message to modern society. Tolkien, a man in the wrong century, was greatly influenced by the Anglo-Saxon as portrayed in the way he lived his life, through his education and teaching, and through the themes and ideas in his works.

At a young age J.R.R. Tolkien already had a taste for languages, so strong that he constructed several of his own, the first of which was elvish. He made up all of the languages used in the Middle-Earth of The Silmarillion, which are rooted in the old Northern European language. This interest of course stemmed from Tolkien having grown up in Great Britain, thought the history of the nation is what ruled his patriotism. He learned how to read Old English and several other ancient European languages. In school, he is remembered as having talked some of his professors into translating ancient Norse in their spare time.

Tolkien’s interest in philology led him to first start work for the New English Dictionary, and in Oxford he became a tutor. Later he worked at Leeds, and eventually became a Professor of Anglo-Saxon in 1925 at Oxford. Here he taught a required Anglo-Saxon class and is as always, much remembered for his speaking style and great lectures. Later on he rose to the position of Merton Professor of English.

While Tolkien did not publish many of his most famed works during his lifetime, he became a renowned in his field. Through his lectures, his translations and some of his early books and critical pieces, he earned for himself a reputation for being one of the greatest English scholars of his time. We see his love for Old English in his lectures on Beowulf, “The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’w Son,” Exodus and Gawain and the Green Knight, to name a few. These pieces also show the incredible amount of history and linguistics studied by Tolkien as a scholar.

“When he lectured, he did so in the dramatic manner of an Anglo-Saxon bard in a mead hall. W.H. Auden wrote to Tolkien: ‘What an unforgettable experience it was for me as an undergraduate, hearing you recite Beowulf. The voice was the voice of Gandalf.’” (booksfactory)

Anglo-Saxon themes run rampant through Tolkien’s works. When Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings, he tried to think of himself translating the story from another language. Norman F. Cantor mentioned that, “Tolkien claimed that he imagined first the language, then the story of the long journey and quest (epic) in that language” (Tompkins). The Anglo-Saxon language that he based his writing on, was spoken until

the Norman Invasion in 1066. The language later evolved to Middle English, spoken in Chaucer and the Canterbury Tales, and then to Modern English around Shakespeare’s time.

Tolkien’s use of runes is an interesting form of writing as well in that though they were firstly Germanic, then later evolved and were used all over Europe. The spread of the Christian faith and Roman/Latin alphabet diminished the use of runes though the so-called, “pagans” continued to use them. The Druid religion especially relied on them, though this led to their persecution by the Christians (Smith 3). In his books, Tolkien used the Anglo-Saxon Runes in The Hobbit for maps and graphics and more importantly for the dwarves. The moon-runes are particularly fun and fascinating, for they are only visible when the moon-light shines upon them, sometimes at a specific time and date.

In the Middle-earth books, Tolkien uses the race of dwarves to symbolize the Anglo-Saxon culture. They are the race that loves gold and riches, they are rough and loud and valiant. They have the mead-halls and are the conquerors of the Celts (the reason for the tension between the dwarves and the elves the books). These are all attributes apparently shared by the Anglo-Saxons, which also occur in the literature of their time period.

“Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” by Tolkien, is one of the most renowned essay’s (lectures) on Beowulf, the first English epic and the most celebrated poem of Old Engish. In the essay, he staunchly protects the book against all critics who would look it from a merely historical and factual view point. He says that only literary

and philological critics could be given any credit when commenting on 17th century Beowulf because it is a work of art, not a historical document.

The Anglo-Saxon themes in Tolkien’s writing are most prominent in The Silmarillion, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. A strong Anglo-Saxon theme runs through the books as they describe a world of epic heroes, forgotten glories and quests for the triumph of good over evil. Mead-halls, funeral songs and epic battles are prevalent in the books, as they frequented the Anglo-Saxon history. Also an interesting topic; Bilbo the hobbit steals a goblet from the dragon in the book, The Hobbit. A similar occurance happens in Beowulf when a cup is also stolen from a dragon. While Tolkien never said that Bilbo and the dragon was based on the story of Beowulf and the dragon, he did mention that, “Beowulf is among my most valued sources” (Carpenter, 31).Looking through the events in Tolkien’s books, it is easy to spot the stories repeated here and there from many forms of Old English literature.

Tolkien’s creation of Arda and the language used there is definitely related to Beowulf. The name of Beorn, the shape-shifting character in The Hobbit, is used in Beowulf and means warrior or hero. Of course it also comes out of Norse mythology and means “bear.” “Middan-geard,” out of Beowulf means “Middle-Earth,” which is also referenced in Exodus. Orc-neas, meaning “Evil Shades” in Old English, is the root word for the Middle-Earth creature, the orc. The people of Rohan were given Anglo-Saxon names such as Eowyn and Folcwine and the dwarves of course were also gifted with such titles.

The most important elements and characters are also shown in these sources. “Lo! We have heard how near and far over middle-earth Moses declared his ordinances to men…” (Exodus, 21) This is the first line of The Old English Exodus, translated by Tolkien. Can it be any more apparent how much influence Old English had on Tolkien’s work? Also, the line from Exodus, “I am that I am,” shows up in The Hobbit when Gandalf says, “I am Gandalf and that is me,” when he turns up at Bilbo’s door. This important Christian document in the skilled hands of Tolkien turns into a beautiful translation that is very different than the Exodus we get in today’s religious learning. This version is rife with the Anglo-Saxon tradition, just reading it directly from Old English puts the reader back in a time of valor, battles and ritual.

While Tolkien uses ancient languages such as Norse, Greco-Roman and Norm, Anglo-Saxon takes the cake when it comes to the most used source for his works. Looking at all of his work, Tolkien’s skill at manipulating the language and history to fit his own myths is fascinating. He is a true genius as is recognized by scholars the world over when it comes to philology. His delicacy with the words such as keeping “dwarfs” and “elfen,” to what he thought should be their true form: “dwarves” and “elven,” is amazing to see because it shows how important the language is to him. Even the personalities and relationships that he gives to his fantasy races is all derived from the historical races of the cultures he’s basing them on: Celt, Anglo-Saxon, and of course Modern English society. Tolkien’s work with Old English literature and myth gives him

the qualification to take it and twist it so that modern day people can get a taste of a vanished and valuable culture.

At a young age J.R.R. Tolkien already had a taste for languages, so strong that he constructed several of his own, the first of which was elvish. He made up all of the languages used in the Middle-Earth of The Silmarillion, which are rooted in the old Northern European language. This interest of course stemmed from Tolkien having grown up in Great Britain, thought the history of the nation is what ruled his patriotism. He learned how to read Old English and several other ancient European languages. In school, he is remembered as having talked some of his professors into translating ancient Norse in their spare time.

Tolkien’s interest in philology led him to first start work for the New English Dictionary, and in Oxford he became a tutor. Later he worked at Leeds, and eventually became a Professor of Anglo-Saxon in 1925 at Oxford. Here he taught a required Anglo-Saxon class and is as always, much remembered for his speaking style and great lectures. Later on he rose to the position of Merton Professor of English.

While Tolkien did not publish many of his most famed works during his lifetime, he became a renowned in his field. Through his lectures, his translations and some of his early books and critical pieces, he earned for himself a reputation for being one of the greatest English scholars of his time. We see his love for Old English in his lectures on Beowulf, “The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’w Son,” Exodus and Gawain and the Green Knight, to name a few. These pieces also show the incredible amount of history and linguistics studied by Tolkien as a scholar.

“When he lectured, he did so in the dramatic manner of an Anglo-Saxon bard in a mead hall. W.H. Auden wrote to Tolkien: ‘What an unforgettable experience it was for me as an undergraduate, hearing you recite Beowulf. The voice was the voice of Gandalf.’” (booksfactory)

Anglo-Saxon themes run rampant through Tolkien’s works. When Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings, he tried to think of himself translating the story from another language. Norman F. Cantor mentioned that, “Tolkien claimed that he imagined first the language, then the story of the long journey and quest (epic) in that language” (Tompkins). The Anglo-Saxon language that he based his writing on, was spoken until

the Norman Invasion in 1066. The language later evolved to Middle English, spoken in Chaucer and the Canterbury Tales, and then to Modern English around Shakespeare’s time.

Tolkien’s use of runes is an interesting form of writing as well in that though they were firstly Germanic, then later evolved and were used all over Europe. The spread of the Christian faith and Roman/Latin alphabet diminished the use of runes though the so-called, “pagans” continued to use them. The Druid religion especially relied on them, though this led to their persecution by the Christians (Smith 3). In his books, Tolkien used the Anglo-Saxon Runes in The Hobbit for maps and graphics and more importantly for the dwarves. The moon-runes are particularly fun and fascinating, for they are only visible when the moon-light shines upon them, sometimes at a specific time and date.

In the Middle-earth books, Tolkien uses the race of dwarves to symbolize the Anglo-Saxon culture. They are the race that loves gold and riches, they are rough and loud and valiant. They have the mead-halls and are the conquerors of the Celts (the reason for the tension between the dwarves and the elves the books). These are all attributes apparently shared by the Anglo-Saxons, which also occur in the literature of their time period.

“Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” by Tolkien, is one of the most renowned essay’s (lectures) on Beowulf, the first English epic and the most celebrated poem of Old Engish. In the essay, he staunchly protects the book against all critics who would look it from a merely historical and factual view point. He says that only literary

and philological critics could be given any credit when commenting on 17th century Beowulf because it is a work of art, not a historical document.

The Anglo-Saxon themes in Tolkien’s writing are most prominent in The Silmarillion, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. A strong Anglo-Saxon theme runs through the books as they describe a world of epic heroes, forgotten glories and quests for the triumph of good over evil. Mead-halls, funeral songs and epic battles are prevalent in the books, as they frequented the Anglo-Saxon history. Also an interesting topic; Bilbo the hobbit steals a goblet from the dragon in the book, The Hobbit. A similar occurance happens in Beowulf when a cup is also stolen from a dragon. While Tolkien never said that Bilbo and the dragon was based on the story of Beowulf and the dragon, he did mention that, “Beowulf is among my most valued sources” (Carpenter, 31).Looking through the events in Tolkien’s books, it is easy to spot the stories repeated here and there from many forms of Old English literature.

Tolkien’s creation of Arda and the language used there is definitely related to Beowulf. The name of Beorn, the shape-shifting character in The Hobbit, is used in Beowulf and means warrior or hero. Of course it also comes out of Norse mythology and means “bear.” “Middan-geard,” out of Beowulf means “Middle-Earth,” which is also referenced in Exodus. Orc-neas, meaning “Evil Shades” in Old English, is the root word for the Middle-Earth creature, the orc. The people of Rohan were given Anglo-Saxon names such as Eowyn and Folcwine and the dwarves of course were also gifted with such titles.

The most important elements and characters are also shown in these sources. “Lo! We have heard how near and far over middle-earth Moses declared his ordinances to men…” (Exodus, 21) This is the first line of The Old English Exodus, translated by Tolkien. Can it be any more apparent how much influence Old English had on Tolkien’s work? Also, the line from Exodus, “I am that I am,” shows up in The Hobbit when Gandalf says, “I am Gandalf and that is me,” when he turns up at Bilbo’s door. This important Christian document in the skilled hands of Tolkien turns into a beautiful translation that is very different than the Exodus we get in today’s religious learning. This version is rife with the Anglo-Saxon tradition, just reading it directly from Old English puts the reader back in a time of valor, battles and ritual.

While Tolkien uses ancient languages such as Norse, Greco-Roman and Norm, Anglo-Saxon takes the cake when it comes to the most used source for his works. Looking at all of his work, Tolkien’s skill at manipulating the language and history to fit his own myths is fascinating. He is a true genius as is recognized by scholars the world over when it comes to philology. His delicacy with the words such as keeping “dwarfs” and “elfen,” to what he thought should be their true form: “dwarves” and “elven,” is amazing to see because it shows how important the language is to him. Even the personalities and relationships that he gives to his fantasy races is all derived from the historical races of the cultures he’s basing them on: Celt, Anglo-Saxon, and of course Modern English society. Tolkien’s work with Old English literature and myth gives him

the qualification to take it and twist it so that modern day people can get a taste of a vanished and valuable culture.

My paper- Orality in Tolkien

“…and they sang before him and he was glad…

they saw a new world…

Behold your music, this is your minstrelsy…”

(Silmarillian 17, Iluvatar)

J.R.R. Tolkien wrote the stories of Middle-Earth to construct a literary forum for his numerous fields of study. Middle-Earth was about his studies, his ideals, and his beliefs, a reflection of a world where humans evolved from their cultural origins. Of these origins, Tolkien found the orality of humanity very important to the world. Tolkien looked back into our societal roots at the people and stories that existed in what we call primitive times, when an oral culture flourished with knowledge and creativity and a memory that is astonishing. Tolkien himself took an acute interest in the people of ancient northern Europe, who were a primary-oral culture. He fashioned his own fantasy world into this same type of environment, where knowledge and memory lives in song, poetry, riddles, and any type of verse to be carried on through time. In Tolkien’s books nestles a fantastical civilization, modeled after real historical cultures, full of the oral tradition in form, style, history, and creativity.

A primary-oral culture is one in which writing does not exist. All information, knowledge and history is put into complex verse and then learned by those whose job it is to carry on the tradition.

Thinking of oral tradition or a heritage of oral performance, genres and styles as ‘oral literature’, is rather like thinking of horses as automobiles without wheels. You can, of course, undertake to do this. Imagine writing a treatise on horses (for people who have never seen a horse) which starts with the concept not of a horse but of ‘automobile’, built on the readers’ direct experience of automobiles. It proceeds to discourse on horses by always referring to them as ‘wheelless automobiles’, explaining to highly automoblized readers who have never seen a horse all the points of difference in an effort to excise all idea of ‘automobile’ out of the concept of ‘wheelless automobile’ so as to invest the term with a purely equine meaning. (Ong, 12)

Of course, Middle-earth is not a world of primary-orality, but the enormous amount of orality used suggests that it was in the beginning. It is only in the modern ages of Middle-Earth that writing has any significance at all. The oral tradition was still prevalent in the books though, and the main source for historical, worldly knowledge, and the society’s emotional center of the people of Middle-Earth.

There are certain elements that go into epic verse and smaller poems that is used to help remember information and make it more accessible to the listener. Almost all of Tokien’s verse have this basic primary-oral form. These methods of memorization or “memory keys,” are used to remember stories such as Beowulf or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The most obvious oral memory keys are repetition, rhythm, epithets, the story within the story, and back-looping.

Repetition is used to ingrain a word or theme into a person’s mind by using it over and over again. Add rhythm and word patterns to this, and the audience gets an easily remembered musical sense of the verse. Epithets, proverbs, and clichés are all used so that a listener can grasp at a recognizable concept. Stories within stories (like Russian dolls-within-dolls or Chinese puzzle boxes) are interconnected, one story leading to another, which leads again to another. The stories flow into each other and necessitate others being told in conjunction. Back-looping is when the storyteller constantly moves back and forth from beginning to end, from repeating idea after idea, so that the audience does not forget the origin of the tale. These are all tricks used in oral cultures, all which Tolkien uses in the poetry of Middle-Earth.

These forms can be observed in such verse as “The Road Goes Ever On,” a poem sung by Bilbo and Frodo in the books. Bilbo is the first who recites it in The Hobbit. A poem written by Tolkien long before the his books, it is a classic song of traveling and returning. Several times it is spoken by Bilbo, and later by Frodo who absorbs and adapts it in The Lord of the Rings. Each time it is performed there are minor changes in the verse to fit accordingly with situation, the place and time, and the audience to whom it is sung.

This is another colorful and important aspect of orality. With the changing of the storyteller, the story changes according to the person’s viewpoint, creative style, and emotional relation to the moment. The performer also modernizes it in a fashion. He adapts the vocabulary so it is digestible, making sure it relates to the audience.

For an oral culture learning or knowing means achieving close, empathetic, communal identification with the known… Writing separates the knower from the known and thus sets up conditions for ‘objectivity’ in the sense of personal disengagement or distancing. (Ong 45)

Finally, the audience needs to be able to understand the verse itself, so it must be made compelling and simple. Again, this can be seen throughout “The Road Goes Ever On” and many other verses of Middle-Earth.

There is writing in Tolkien such as dwarf runes, the library at Isengard, and the historical scrolls. In fact, almost all races have a written language. Even so, Tolkien obviously finds it very important to manifest the oral culture within Middle-Earth. He knows the significance of orality in the linguistic history of Old English culture which he is using. Being a professor of linguistics, Tolkien took a special interest in northern European cultures. The Anglo-Saxons, the Goths, the Normans, to name a few, were people that he intensely studied.

Tolkien himself has played a major role by working with the literature that came out of the orality of the time. He translated the Anglo-Saxon Exodus as well as Gawain and the Green Knight and The Homecoming of Beortnoth, Beorhthelm’s Son, among others. He also taught this genre, giving famous lectures and writing ingenious essays on stories such as Beowulf and The Pearl. The cultures that created these stories revolved around their use of songs and chant. There is always the vivid image of the Anglo-Saxon men in mead halls, bursting with songs of valor, heroism, honor, death, and triumph. We can definitely see these characteristics in the race of the Rohirim, the dwarves and in the men of Gondor.

In the world of Middle-earth, language has actual physical power. Tolkien, always a scholar and a Catholic, was well-versed in religion and the Bible. He might have taken religious ideas into account when he gave language this power. The story of the people of Babel, who were unified with one common language, built a tower to heaven, and when God discovered this He smote it down and in his wrath. He then divided the language of the people so that they could never again attain such power. In this way, when God took away language, He took away power.

Also, in the event of one people conquering another, there is always the factor of how to integrate them into the new society so that they cannot unify and revolt. So, the Egyptians took away the language of the Jews. The English made it illegal for the Irish, the Scots, and the Welsh to speak or write in their own language thus, the language was forgotten. With the loss of language comes the loss of stories and therefore history. Thus, the culture is stripped of its very essence and instead mixed with the new. How can a people unite if they no longer have individuality and freedom. Without language, how can they remember who they are? It is in Tolkien’s books that this power is played out.

When Gandalf speaks at the Council of Elrond, his words are power. As Gandalf speaks the language of Mordor, it actually has a real effect. He has conjured an evil through the language.

“The change in the wizard’s voice was astounding. Suddenly it became menacing, powerful, harsh as stone. A shadow seemed to pass over the high sun, and the porch for a moment grew dark. All trembled, and the Elves stopped their ears.” (Tolkien, 248)

A damned language such as this dark Elvish, might manifest the very evil itself, and the elves, knowing this were angry with Gandalf for having endangered them all.

Names also hold power in Tolkien’s works. Another biblical explanation for this might be that in the Bible; God does not even say his own name, but instead says “I am.” Nor are his worshippers alowed to say his name; even in modern times the Christian will not “take the Lords name in vain.” To do this may invoke the wrath of God. When Christ wants to hold political sway, he calls upon the names of his forefathers: David, Abraham, Adam, so that he may have their power, though he too incurs their sins. Gandalf always refers to characters by their names and then the names of their father, such as; “Gimli son of Gloin.” Names are always of importance in Tolkien. To give a name is to give the recipient power over you. To be given a name is to take on the characteristics of that name. Gollum “Sneak” becomes a sneak; “Strider” becomes “Wind-walker,” as he must travel quickly.

When Gollum is caught by the agents of the dark-lord, with torture he is forced to utter through his grimy lips, “Baggins!” and “Shire!” With these words the evil-doers can then locate the ring and start on their journey. Another example is when Thingol, Luthien’s father, curses Beren in The Silmarillion. Beren refuses to take the names onto himself when Thingol does this. “Death you can give me earned or unearned; but names I will not take from you of baseborn, nor spy, nor thrall.” (The Silmarillion, 167) In this way, Thingol’s names cannot define being of Beren.

Of course, the real importance of orality that jumps to mind when the history of Middle-earth comes to mind is its creation. Eru/Iluvatar makes the Ainur/Valar who sing Arda/Middle-earth into existence. Through each of their individual melodies, the three harmonies create the world. The power of song is the power of creation. This makes it quite apparent then, how song and orality is based in the very existence of the earth.

Orality is used throughout history whether it is to invoke evil and good, to mourn or to remember people and events past. Interestingly enough, many of the songs, lays, poems or riddles are related to actual real English lore. Old nursery rhymes and fairy tales are woven into the orality of Middle-earth, as if that is where they originated in the first place, or maybe to demonstrate where all fairy tales come from. In The Silmarillion, when Luthien is trapped in her house, she uses her long hair to escape, like the story of Rapunzel. The Middle-earth song, “The Man on the Moon Came Down too Soon,” is a longer and more descriptive version of “Hey Diddle Diddle, the Cat and the Fiddle.”

Tolkien seems to revere the origins of oral culture to a high degree, whether that is because of his love of language or his study of primary oral culture. It shows up in every single one of his written works and in his oral dialogue. In inventing this fictional oral culture, he has again conjured admiration for the oral tradition. In every song and story in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the reader is sent down a road of history, into the heart of the world.

they saw a new world…

Behold your music, this is your minstrelsy…”

(Silmarillian 17, Iluvatar)

J.R.R. Tolkien wrote the stories of Middle-Earth to construct a literary forum for his numerous fields of study. Middle-Earth was about his studies, his ideals, and his beliefs, a reflection of a world where humans evolved from their cultural origins. Of these origins, Tolkien found the orality of humanity very important to the world. Tolkien looked back into our societal roots at the people and stories that existed in what we call primitive times, when an oral culture flourished with knowledge and creativity and a memory that is astonishing. Tolkien himself took an acute interest in the people of ancient northern Europe, who were a primary-oral culture. He fashioned his own fantasy world into this same type of environment, where knowledge and memory lives in song, poetry, riddles, and any type of verse to be carried on through time. In Tolkien’s books nestles a fantastical civilization, modeled after real historical cultures, full of the oral tradition in form, style, history, and creativity.

A primary-oral culture is one in which writing does not exist. All information, knowledge and history is put into complex verse and then learned by those whose job it is to carry on the tradition.

Thinking of oral tradition or a heritage of oral performance, genres and styles as ‘oral literature’, is rather like thinking of horses as automobiles without wheels. You can, of course, undertake to do this. Imagine writing a treatise on horses (for people who have never seen a horse) which starts with the concept not of a horse but of ‘automobile’, built on the readers’ direct experience of automobiles. It proceeds to discourse on horses by always referring to them as ‘wheelless automobiles’, explaining to highly automoblized readers who have never seen a horse all the points of difference in an effort to excise all idea of ‘automobile’ out of the concept of ‘wheelless automobile’ so as to invest the term with a purely equine meaning. (Ong, 12)

Of course, Middle-earth is not a world of primary-orality, but the enormous amount of orality used suggests that it was in the beginning. It is only in the modern ages of Middle-Earth that writing has any significance at all. The oral tradition was still prevalent in the books though, and the main source for historical, worldly knowledge, and the society’s emotional center of the people of Middle-Earth.

There are certain elements that go into epic verse and smaller poems that is used to help remember information and make it more accessible to the listener. Almost all of Tokien’s verse have this basic primary-oral form. These methods of memorization or “memory keys,” are used to remember stories such as Beowulf or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The most obvious oral memory keys are repetition, rhythm, epithets, the story within the story, and back-looping.

Repetition is used to ingrain a word or theme into a person’s mind by using it over and over again. Add rhythm and word patterns to this, and the audience gets an easily remembered musical sense of the verse. Epithets, proverbs, and clichés are all used so that a listener can grasp at a recognizable concept. Stories within stories (like Russian dolls-within-dolls or Chinese puzzle boxes) are interconnected, one story leading to another, which leads again to another. The stories flow into each other and necessitate others being told in conjunction. Back-looping is when the storyteller constantly moves back and forth from beginning to end, from repeating idea after idea, so that the audience does not forget the origin of the tale. These are all tricks used in oral cultures, all which Tolkien uses in the poetry of Middle-Earth.

These forms can be observed in such verse as “The Road Goes Ever On,” a poem sung by Bilbo and Frodo in the books. Bilbo is the first who recites it in The Hobbit. A poem written by Tolkien long before the his books, it is a classic song of traveling and returning. Several times it is spoken by Bilbo, and later by Frodo who absorbs and adapts it in The Lord of the Rings. Each time it is performed there are minor changes in the verse to fit accordingly with situation, the place and time, and the audience to whom it is sung.

This is another colorful and important aspect of orality. With the changing of the storyteller, the story changes according to the person’s viewpoint, creative style, and emotional relation to the moment. The performer also modernizes it in a fashion. He adapts the vocabulary so it is digestible, making sure it relates to the audience.

For an oral culture learning or knowing means achieving close, empathetic, communal identification with the known… Writing separates the knower from the known and thus sets up conditions for ‘objectivity’ in the sense of personal disengagement or distancing. (Ong 45)

Finally, the audience needs to be able to understand the verse itself, so it must be made compelling and simple. Again, this can be seen throughout “The Road Goes Ever On” and many other verses of Middle-Earth.

There is writing in Tolkien such as dwarf runes, the library at Isengard, and the historical scrolls. In fact, almost all races have a written language. Even so, Tolkien obviously finds it very important to manifest the oral culture within Middle-Earth. He knows the significance of orality in the linguistic history of Old English culture which he is using. Being a professor of linguistics, Tolkien took a special interest in northern European cultures. The Anglo-Saxons, the Goths, the Normans, to name a few, were people that he intensely studied.

Tolkien himself has played a major role by working with the literature that came out of the orality of the time. He translated the Anglo-Saxon Exodus as well as Gawain and the Green Knight and The Homecoming of Beortnoth, Beorhthelm’s Son, among others. He also taught this genre, giving famous lectures and writing ingenious essays on stories such as Beowulf and The Pearl. The cultures that created these stories revolved around their use of songs and chant. There is always the vivid image of the Anglo-Saxon men in mead halls, bursting with songs of valor, heroism, honor, death, and triumph. We can definitely see these characteristics in the race of the Rohirim, the dwarves and in the men of Gondor.

In the world of Middle-earth, language has actual physical power. Tolkien, always a scholar and a Catholic, was well-versed in religion and the Bible. He might have taken religious ideas into account when he gave language this power. The story of the people of Babel, who were unified with one common language, built a tower to heaven, and when God discovered this He smote it down and in his wrath. He then divided the language of the people so that they could never again attain such power. In this way, when God took away language, He took away power.

Also, in the event of one people conquering another, there is always the factor of how to integrate them into the new society so that they cannot unify and revolt. So, the Egyptians took away the language of the Jews. The English made it illegal for the Irish, the Scots, and the Welsh to speak or write in their own language thus, the language was forgotten. With the loss of language comes the loss of stories and therefore history. Thus, the culture is stripped of its very essence and instead mixed with the new. How can a people unite if they no longer have individuality and freedom. Without language, how can they remember who they are? It is in Tolkien’s books that this power is played out.

When Gandalf speaks at the Council of Elrond, his words are power. As Gandalf speaks the language of Mordor, it actually has a real effect. He has conjured an evil through the language.

“The change in the wizard’s voice was astounding. Suddenly it became menacing, powerful, harsh as stone. A shadow seemed to pass over the high sun, and the porch for a moment grew dark. All trembled, and the Elves stopped their ears.” (Tolkien, 248)

A damned language such as this dark Elvish, might manifest the very evil itself, and the elves, knowing this were angry with Gandalf for having endangered them all.

Names also hold power in Tolkien’s works. Another biblical explanation for this might be that in the Bible; God does not even say his own name, but instead says “I am.” Nor are his worshippers alowed to say his name; even in modern times the Christian will not “take the Lords name in vain.” To do this may invoke the wrath of God. When Christ wants to hold political sway, he calls upon the names of his forefathers: David, Abraham, Adam, so that he may have their power, though he too incurs their sins. Gandalf always refers to characters by their names and then the names of their father, such as; “Gimli son of Gloin.” Names are always of importance in Tolkien. To give a name is to give the recipient power over you. To be given a name is to take on the characteristics of that name. Gollum “Sneak” becomes a sneak; “Strider” becomes “Wind-walker,” as he must travel quickly.

When Gollum is caught by the agents of the dark-lord, with torture he is forced to utter through his grimy lips, “Baggins!” and “Shire!” With these words the evil-doers can then locate the ring and start on their journey. Another example is when Thingol, Luthien’s father, curses Beren in The Silmarillion. Beren refuses to take the names onto himself when Thingol does this. “Death you can give me earned or unearned; but names I will not take from you of baseborn, nor spy, nor thrall.” (The Silmarillion, 167) In this way, Thingol’s names cannot define being of Beren.

Of course, the real importance of orality that jumps to mind when the history of Middle-earth comes to mind is its creation. Eru/Iluvatar makes the Ainur/Valar who sing Arda/Middle-earth into existence. Through each of their individual melodies, the three harmonies create the world. The power of song is the power of creation. This makes it quite apparent then, how song and orality is based in the very existence of the earth.

Orality is used throughout history whether it is to invoke evil and good, to mourn or to remember people and events past. Interestingly enough, many of the songs, lays, poems or riddles are related to actual real English lore. Old nursery rhymes and fairy tales are woven into the orality of Middle-earth, as if that is where they originated in the first place, or maybe to demonstrate where all fairy tales come from. In The Silmarillion, when Luthien is trapped in her house, she uses her long hair to escape, like the story of Rapunzel. The Middle-earth song, “The Man on the Moon Came Down too Soon,” is a longer and more descriptive version of “Hey Diddle Diddle, the Cat and the Fiddle.”

Tolkien seems to revere the origins of oral culture to a high degree, whether that is because of his love of language or his study of primary oral culture. It shows up in every single one of his written works and in his oral dialogue. In inventing this fictional oral culture, he has again conjured admiration for the oral tradition. In every song and story in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the reader is sent down a road of history, into the heart of the world.

This is a cool site talking about the brain and memory. It has some awsome stories and examples of people with extraordinary memory gifts: http://www.exploratorium.edu/memory/

This is a great site for my beloved Isabelle Allende: http://www.isabelallende.com/

This is a great site for my beloved Isabelle Allende: http://www.isabelallende.com/

The Brothers K and memory!

Ok here is a great essay to check out!!!

This refers to the Brothers K and how the importance of memory is brought up in the end!

http://www.dartmouth.edu/~karamazo/sheehan.html

sample:

Central to Eastern Orthodox Christendom is the singing, at the end of every Orthodox funeral, of the song known as "Memory Eternal" (in Church Slavonic: Vechnaya Pamyat). This song also concludes Dostoevsky's great, final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, when, following the funeral of the boy whom Alyosha Karamazov (and the circle of schoolboys around Alyosha) had deeply loved, Alyosha speaks to the boys about the funeral and about the meaning of the resurrection, with this brief song as their steady focus.

This refers to the Brothers K and how the importance of memory is brought up in the end!

http://www.dartmouth.edu/~karamazo/sheehan.html

sample:

Central to Eastern Orthodox Christendom is the singing, at the end of every Orthodox funeral, of the song known as "Memory Eternal" (in Church Slavonic: Vechnaya Pamyat). This song also concludes Dostoevsky's great, final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, when, following the funeral of the boy whom Alyosha Karamazov (and the circle of schoolboys around Alyosha) had deeply loved, Alyosha speaks to the boys about the funeral and about the meaning of the resurrection, with this brief song as their steady focus.

Magical Realism and Oral Traditions

Some of my favorite books of all time fall into the category of "magical realism" (I found out this semester).

Now you may ask, how does this relate to Oral Traditions and I would answer you this:

Because when one reads a book with the element of "magical realism," one gets the feeling that a very old and wise storyteller is sitting right across the table, relating the tales of his life for you to hear. The element of reading seems to almost vanish, as the vivid detail seems to speak out loud.

I am concerned when people call it fantasy (not that I don't love to read fantasy), because magical realism is quite different while still holding the same appeal. It is more like real, practical and everyday life being expressed in a fantastical way. It does not contain any elements of a fantasy world such as magic powers, or unicorns, atleast not in a physical sense. The fantasy element in a magical realism novel is more mystery and enigma. It is stuff from peoples cultural legends- so while it may seem unreal or a tall tale, it is taken from the human life world and from the natural world.

Example: In "The House of Spirits," when the old farmer on the South American ranch deals with the ant problem, he doesn't get insecticide, he simply picks up the ant, speaks very kindly to it in his cupped palm to take his friends, and then my the next day all the ants are gone.

Or in the same novel, Clara's wild uncle picks up a puppy in a distant land and brings it back small dirty and shivering. It then grows up to be the size of a small horse and unrecognizable as any breed known.

For anyone who hasn't ventured into the world of magical realism, you should! (Especially since several very important books in this category (One Hundred Years of Solitude, Metamorphosis (Kafka)) or on our Top One Hundred list!

Here is a list I pulled off a site when I was looking a magical realism stuff:

A Long List -

Aitmatov, Chingiz (USSR) The Day Lasts More Than A Hundred Years [fg]

Alexie, Sherman (?) Reseration Blues [np]

Allende, Isobel (Chile) House of the Spirits [np]

Allende, Isobel (Chile) Love and Shadows [fg]

Beagle, Peter (US) A Fine and Private Place [ew]

Bell, Douglas Mojo and the Pickle Jar [ew]

Billias, Stephen The Quest for the 36 [ew]

Bisson, Terry (US) Talking Man [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) All the Bells on Earth [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) The Digging Leviathan [ts]

Blaylock, James (US) Night Relics [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) Paper Grail [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) The Last Coin [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) The Rainy Season [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) Winter Tides [ew]

Bradbury, Ray (US) Dandelion Wine [ew]

Bradbury, Ray (US) [others] [ew]

Bulgakov, Mikhail (Russia) The Master and Margarita [sm]

Byatt, A. S. (UK) The Djinn in the Nightingale's Eye [ew]

Cabell, James Branch (US) The Cream of the Jest [ew]

Cabell, James Branch (US) [others] [ew]

Calvino, Italo (Italy) Numbers in the Dark [ew]

Calvino, Italo (Italy) The Watcher & Other Stories [ew]

Carey, Peter (Australia) Illywhacker [fg]

Carroll, Jonathan (UK) [ew,gec]

Carter, Angela (UK) Burning Your Boats: The Collected Short Stories [soh]

Carter, Angela (UK) Nights at the Circus [fg,np,soh]

Castillo, Anna (?) So Far from God [np]

Chamoiseau, Patrick (?) Texaco [np]

Charnas, Suzy McKee (US) Dorothea Dreams [ew]

Cheever, John (US) "The Swimmer" [rm]

Chesterton, G. K. (UK) The Man Who Was Thursday [ew]

Crowley, John (US) Little, Big [ew]

Crowley, John (US) [others] [ew]

Davidson, Avram (US) [ecl]

De Lint, Charles (Canada) "Newford" stories [dt]

Delany, Samuel R. (US) Dahlgren [ts]

DeMarinis, Rick (US) Cinder [ew]

Doctorov, E L (US) Loon Lake [fg,np]

Eco, Umberto (Italy) Foucault's Pendulum [fg,soh]

Esquivel, Linda (Mexico) Like Water for Chocolate [dt,rh]

Finney, Charles (US) The Circus of Dr. Lao [ew]

Fowles, John (UK) A Maggot [fg]

García Márquez, Gabriel (Colombia) One Hundred Years of Solitude [everyone]

Gearhardt, Sally M (US) The Wanderground [fg]

Golding, William (UK) The Paper Men [fg]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) Dark Cities Underground [ew]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) The Red Magician [jn]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) Tourists [dn,jn]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) Walking the Labyrinth [jn]

Grant, Richard (US) Tex and Molly in the Afterlife [ew]

Grant, Richard (US) [maybe others] [ew]

Greenland, Colin (UK) Other Voices [fg]

Herrick, Amy (?) At the Sign of the Naked Waiter [np]

Hesse, Herman (Germany) Magister Ludi [fg]

Hoban, Russell (US/UK) The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz] [ew]

Hoban, Russell (US/UK) The Medusa Frequency [fg]

Hoban, Russell (US/UK) [others] [ew]

Hoeg, Peter (Denmark) The History of Danish Dreams [fg]

Hoffman, Alice (US) Illumination Night [np]

Hoffman, Alice (US) Practical Magic [rm]

Hospital, Janette T (Australia) The Last Magician [fg]

Hulme, Keri (New Zealand?) The Bone People [em]

Kafka, Franz (Czech) Metamorphosis [fg]

Kathryns, G. A. The Borders of Life [ew]

Kinsella, W. P. (US) Shoeless Joe [dt]

Knudtsen, Ingar (Norway) [son]

Kotzwinkle, William (US) The Bear Went over the Mountain [nl]

Kundera, Milan (Czech) Immortality [fg,np,rh]

Lafferty, R. A. (US) [ew]

Le Guin, Ursula K (US) Threshold [fg]

Lessing, Doris (UK) The Memoirs of a Survivor [fg]

Lindholm, Megan (US) Wizard of the Pigeons [ew,jn]

Machen, Arthur (UK/Wales) The Hill of Dreams [ew]

Machen, Arthur (UK/Wales) The Three Imposters [ew]

McCammon, Robert (US) A Boy's Life [ba]

McCarthy, Cormac (US) Blood Meridian [das]

McEwan, Ian (UK) The Child in Time [fg,np]

Millhauser, Steven The Barnum Museum [ew]

Millhauser, Steven In the Penny Arcade [ew]

Millhauser, Steven The Knife Thrower and Other Stories [ew]

Millhauser, Steven Little Kingdoms [ew]

Morrison, Toni (US) Beloved

Morrison, Toni (US) Paradise [das]

Morrison, Toni (US) Sula

Naylor, Gloria (?) Bailey's Cafe [np]

Nordan, Lewis (US) Lightning Song [das]

Nordan, Lewis (US) Wolf Whistle [das]

O'Brien, Flann (Ireland) The Third Policeman [ew]

Okri, Ben (Nigeria) The Famished Road [je]

Parsipur, Sharnush (Iran) [jb]

Peake, Mervyn (UK) Mr. Pye [ew]

Powers, Tim (US) Earthquake Weather [ew]

Powers, Tim (US) Expiration Date [ew]

Powers, Tim (US) Last Call [ew]

Puig, Manuel (Argentina) [rh]

Ransmayer, Christoph (Austria) The Last World [fg]

Read, Herbert (UK) The Green Child [ew,fg]

Ruff, Matt The Fool on the Hill [ew]

Rushdie, Salman (UK/India) Midnight's Children and Shame [fg,np]

Saramago, Jose (Portugal) [das]

Saxton, Josephine (UK/US) Queen of the States [fg]

Singer, Isaac Bashevis [vs]

Skibell, Jospeh A Blessing on the Moon [np]

Smith, Thorne The Lost Lamb [ew]

Smith, Thorne Rain in the Doorway [ew]

Stewart, Sean (US) Galveston [ew]

Stewart, Sean (US) Resurrection Man [ew]

Swanwick, Michael (US) Stations of the Tide [frossie]

Swift, Graham (UK) Waterland [fg,np]

Tepper, Sheri (US) "Marianne" books [eam,jw]

Tepper, Sheri (US) Beauty [eam,jw]

Thornton, Lawrence (?) Imagining Argentina [np]

Tutuola, Amos (Nigeria) The Palm Wine Drinkard [sc]

Vargas Llosa, Mario (Peru) [rh]

Warner, Sylvia Townsend Lolly Willowes [ew]

White, T. H. (UK) The Elephant and the Kangaroo [ew]

White, T. H. (UK) Mistress Masham's Repose [ew]

Williams, Charles (UK) [ew]

Winton, Tim (?) Cloudstreet [np]

Wolfe, Gene (US) The Devil in a Forest [ew]

Wolfe, Gene (US) Free Live Free [ew]

Wolfe, Gene (US) Peace [ew]

Wolfe, Gene (US) Soldier of the Mist [dn,jn]

Wolfe, Gene (US) There Are Doors [ew]

Woolf, Virginia (UK) Orlando [ew]

Now you may ask, how does this relate to Oral Traditions and I would answer you this:

Because when one reads a book with the element of "magical realism," one gets the feeling that a very old and wise storyteller is sitting right across the table, relating the tales of his life for you to hear. The element of reading seems to almost vanish, as the vivid detail seems to speak out loud.

I am concerned when people call it fantasy (not that I don't love to read fantasy), because magical realism is quite different while still holding the same appeal. It is more like real, practical and everyday life being expressed in a fantastical way. It does not contain any elements of a fantasy world such as magic powers, or unicorns, atleast not in a physical sense. The fantasy element in a magical realism novel is more mystery and enigma. It is stuff from peoples cultural legends- so while it may seem unreal or a tall tale, it is taken from the human life world and from the natural world.

Example: In "The House of Spirits," when the old farmer on the South American ranch deals with the ant problem, he doesn't get insecticide, he simply picks up the ant, speaks very kindly to it in his cupped palm to take his friends, and then my the next day all the ants are gone.

Or in the same novel, Clara's wild uncle picks up a puppy in a distant land and brings it back small dirty and shivering. It then grows up to be the size of a small horse and unrecognizable as any breed known.

For anyone who hasn't ventured into the world of magical realism, you should! (Especially since several very important books in this category (One Hundred Years of Solitude, Metamorphosis (Kafka)) or on our Top One Hundred list!

Here is a list I pulled off a site when I was looking a magical realism stuff:

A Long List -

Aitmatov, Chingiz (USSR) The Day Lasts More Than A Hundred Years [fg]

Alexie, Sherman (?) Reseration Blues [np]

Allende, Isobel (Chile) House of the Spirits [np]

Allende, Isobel (Chile) Love and Shadows [fg]

Beagle, Peter (US) A Fine and Private Place [ew]

Bell, Douglas Mojo and the Pickle Jar [ew]

Billias, Stephen The Quest for the 36 [ew]

Bisson, Terry (US) Talking Man [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) All the Bells on Earth [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) The Digging Leviathan [ts]

Blaylock, James (US) Night Relics [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) Paper Grail [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) The Last Coin [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) The Rainy Season [ew]

Blaylock, James (US) Winter Tides [ew]

Bradbury, Ray (US) Dandelion Wine [ew]

Bradbury, Ray (US) [others] [ew]

Bulgakov, Mikhail (Russia) The Master and Margarita [sm]

Byatt, A. S. (UK) The Djinn in the Nightingale's Eye [ew]

Cabell, James Branch (US) The Cream of the Jest [ew]

Cabell, James Branch (US) [others] [ew]

Calvino, Italo (Italy) Numbers in the Dark [ew]

Calvino, Italo (Italy) The Watcher & Other Stories [ew]

Carey, Peter (Australia) Illywhacker [fg]

Carroll, Jonathan (UK) [ew,gec]

Carter, Angela (UK) Burning Your Boats: The Collected Short Stories [soh]

Carter, Angela (UK) Nights at the Circus [fg,np,soh]

Castillo, Anna (?) So Far from God [np]

Chamoiseau, Patrick (?) Texaco [np]

Charnas, Suzy McKee (US) Dorothea Dreams [ew]

Cheever, John (US) "The Swimmer" [rm]

Chesterton, G. K. (UK) The Man Who Was Thursday [ew]

Crowley, John (US) Little, Big [ew]

Crowley, John (US) [others] [ew]

Davidson, Avram (US) [ecl]

De Lint, Charles (Canada) "Newford" stories [dt]

Delany, Samuel R. (US) Dahlgren [ts]

DeMarinis, Rick (US) Cinder [ew]

Doctorov, E L (US) Loon Lake [fg,np]

Eco, Umberto (Italy) Foucault's Pendulum [fg,soh]

Esquivel, Linda (Mexico) Like Water for Chocolate [dt,rh]

Finney, Charles (US) The Circus of Dr. Lao [ew]

Fowles, John (UK) A Maggot [fg]

García Márquez, Gabriel (Colombia) One Hundred Years of Solitude [everyone]

Gearhardt, Sally M (US) The Wanderground [fg]

Golding, William (UK) The Paper Men [fg]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) Dark Cities Underground [ew]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) The Red Magician [jn]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) Tourists [dn,jn]

Goldstein, Lisa (US) Walking the Labyrinth [jn]

Grant, Richard (US) Tex and Molly in the Afterlife [ew]

Grant, Richard (US) [maybe others] [ew]

Greenland, Colin (UK) Other Voices [fg]

Herrick, Amy (?) At the Sign of the Naked Waiter [np]

Hesse, Herman (Germany) Magister Ludi [fg]

Hoban, Russell (US/UK) The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz] [ew]

Hoban, Russell (US/UK) The Medusa Frequency [fg]

Hoban, Russell (US/UK) [others] [ew]

Hoeg, Peter (Denmark) The History of Danish Dreams [fg]

Hoffman, Alice (US) Illumination Night [np]

Hoffman, Alice (US) Practical Magic [rm]

Hospital, Janette T (Australia) The Last Magician [fg]

Hulme, Keri (New Zealand?) The Bone People [em]

Kafka, Franz (Czech) Metamorphosis [fg]

Kathryns, G. A. The Borders of Life [ew]

Kinsella, W. P. (US) Shoeless Joe [dt]

Knudtsen, Ingar (Norway) [son]

Kotzwinkle, William (US) The Bear Went over the Mountain [nl]

Kundera, Milan (Czech) Immortality [fg,np,rh]

Lafferty, R. A. (US) [ew]

Le Guin, Ursula K (US) Threshold [fg]

Lessing, Doris (UK) The Memoirs of a Survivor [fg]

Lindholm, Megan (US) Wizard of the Pigeons [ew,jn]

Machen, Arthur (UK/Wales) The Hill of Dreams [ew]

Machen, Arthur (UK/Wales) The Three Imposters [ew]

McCammon, Robert (US) A Boy's Life [ba]

McCarthy, Cormac (US) Blood Meridian [das]

McEwan, Ian (UK) The Child in Time [fg,np]

Millhauser, Steven The Barnum Museum [ew]

Millhauser, Steven In the Penny Arcade [ew]

Millhauser, Steven The Knife Thrower and Other Stories [ew]

Millhauser, Steven Little Kingdoms [ew]

Morrison, Toni (US) Beloved

Morrison, Toni (US) Paradise [das]

Morrison, Toni (US) Sula

Naylor, Gloria (?) Bailey's Cafe [np]

Nordan, Lewis (US) Lightning Song [das]

Nordan, Lewis (US) Wolf Whistle [das]

O'Brien, Flann (Ireland) The Third Policeman [ew]

Okri, Ben (Nigeria) The Famished Road [je]

Parsipur, Sharnush (Iran) [jb]

Peake, Mervyn (UK) Mr. Pye [ew]

Powers, Tim (US) Earthquake Weather [ew]

Powers, Tim (US) Expiration Date [ew]

Powers, Tim (US) Last Call [ew]

Puig, Manuel (Argentina) [rh]

Ransmayer, Christoph (Austria) The Last World [fg]

Read, Herbert (UK) The Green Child [ew,fg]

Ruff, Matt The Fool on the Hill [ew]

Rushdie, Salman (UK/India) Midnight's Children and Shame [fg,np]

Saramago, Jose (Portugal) [das]

Saxton, Josephine (UK/US) Queen of the States [fg]

Singer, Isaac Bashevis [vs]

Skibell, Jospeh A Blessing on the Moon [np]

Smith, Thorne The Lost Lamb [ew]

Smith, Thorne Rain in the Doorway [ew]

Stewart, Sean (US) Galveston [ew]

Stewart, Sean (US) Resurrection Man [ew]

Swanwick, Michael (US) Stations of the Tide [frossie]

Swift, Graham (UK) Waterland [fg,np]

Tepper, Sheri (US) "Marianne" books [eam,jw]

Tepper, Sheri (US) Beauty [eam,jw]

Thornton, Lawrence (?) Imagining Argentina [np]

Tutuola, Amos (Nigeria) The Palm Wine Drinkard [sc]

Vargas Llosa, Mario (Peru) [rh]

Warner, Sylvia Townsend Lolly Willowes [ew]

White, T. H. (UK) The Elephant and the Kangaroo [ew]

White, T. H. (UK) Mistress Masham's Repose [ew]

Williams, Charles (UK) [ew]

Winton, Tim (?) Cloudstreet [np]

Wolfe, Gene (US) The Devil in a Forest [ew]

Wolfe, Gene (US) Free Live Free [ew]

Wolfe, Gene (US) Peace [ew]

Wolfe, Gene (US) Soldier of the Mist [dn,jn]

Wolfe, Gene (US) There Are Doors [ew]

Woolf, Virginia (UK) Orlando [ew]

Monday, April 04, 2005

Monday, March 21, 2005

Oh, by the way...

I loved Salmon Rushdie- very impressive, I've been meaning to write something about him here, but it will still have to wait!

I loved his description the oral traditions- the juggler, the story tellers with the tricks... he was a fine juggler himself.

Beautiful writer and astounding speaker. It was an unforgettable experience.

NPR with C.S. Lewis

I just got done listening to a program about C.S. Lewis on NPR 102.1 fm from the Cambridge Forum about the Screwtape Letters. It was pretty interesting, I missed hearing the woman-Kathleen something or other who spoke first but I did hear the thoughts of a Peter Craift (sp? author of The Shadowlands of C.S. Lewis among other works) and Armand Nicoli.

Craift spoke about how C.S. Lewis started off as an athiest for the first half of his life. He was learned in philosophy and studied Freud. He used the arguments and questions of Freud to justify his athiesm. Then, after his conversion, Lewis started taking Freuds questions, and started answering them with his own intuitive and spiritual answers.

While Freud reduced Love to Libido,

Lewis wrote about the state of "being in love" vs. Love in the more mature sense of the word. He said that being in love is what brings people together, but it doesn't last. What grows out of it, mature care and will for another person is what keeps people together. There are more reason's to stay married than "being in love."

Also another thing that Lewis was convinced of, one must shut out the worries of the past and future and encapsulate yourself in the present.

Nicoli spoke about Lewis as a philosopher and about his admirable qualities. The Good (love, charity), The True (intellect, reason, faith) and The Beautiful (heart, emotion, imagination) . C.S. Lewis, in the eyes of Nicoli had all of these qualities in spades.